A rocket design can be as simple as a cardboard tube filled with black powder, but to make an efficient, accurate rocket or missile involves overcoming a number of difficult problems. The main difficulties include cooling the combustion chamber, pumping the fuel (in the case of a liquid fuel), and controlling and correcting the direction of motion.[20]

Components

Rockets consist of a propellant, a place to put propellant (such as a propellant tank), and a nozzle. They may also have one or more rocket engines, directional stabilization device(s) (such as fins, vernier engines or engine gimbals for thrust vectoring, gyroscopes) and a structure (typically monocoque) to hold these components together. Rockets intended for high speed atmospheric use also have an aerodynamic fairing such as a nose cone, which usually holds the payload.[21]

As well as these components, rockets can have any number of other components, such as wings (rocketplanes), parachutes, wheels (rocket cars), even, in a sense, a person (rocket belt). Vehicles frequently possess navigation systems and guidance systems that typically use satellite navigation and inertial navigation systems.

Engines

Rocket engines employ the principle of jet propulsion.[2] The rocket engines powering rockets come in a great variety of different types; a comprehensive list can be found in the main article, Rocket engine. Most current rockets are chemically powered rockets (usually internal combustion engines,[22] but some employ a decomposing monopropellant) that emit a hot exhaust gas. A rocket engine can use gas propellants, solid propellant, liquid propellant, or a hybrid mixture of both solid and liquid. Some rockets use heat or pressure that is supplied from a source other than the chemical reaction of propellant(s), such as steam rockets, solar thermal rockets, nuclear thermal rocket engines or simple pressurized rockets such as water rocket or cold gas thrusters. With combustive propellants a chemical reaction is initiated between the fuel and the oxidizer in the combustion chamber, and the resultant hot gases accelerate out of a rocket engine nozzle (or nozzles) at the rearward-facing end of the rocket. The acceleration of these gases through the engine exerts force ("thrust") on the combustion chamber and nozzle, propelling the vehicle (according to Newton's Third Law). This actually happens because the force (pressure times area) on the combustion chamber wall is unbalanced by the nozzle opening; this is not the case in any other direction. The shape of the nozzle also generates force by directing the exhaust gas along the axis of the rocket.[2]

Propellant

Rocket propellant is mass that is stored, usually in some form of propellant tank or casing, prior to being used as the propulsive mass that is ejected from a rocket engine in the form of a fluid jet to produce thrust.[2] For chemical rockets often the propellants are a fuel such as liquid hydrogen or kerosene burned with an oxidizer such as liquid oxygen or nitric acid to produce large volumes of very hot gas. The oxidiser is either kept separate and mixed in the combustion chamber, or comes premixed, as with solid rockets.

Sometimes the propellant is not burned but still undergoes a chemical reaction, and can be a 'monopropellant' such as hydrazine, nitrous oxide or hydrogen peroxide that can be catalytically decomposed to hot gas.

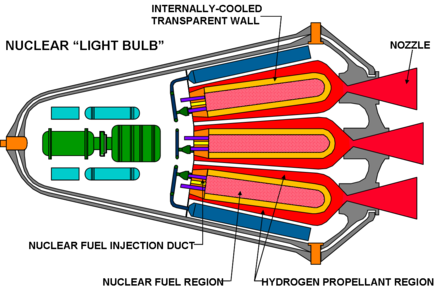

Alternatively, an inert propellant can be used that can be externally heated, such as in steam rocket, solar thermal rocket or nuclear thermal rockets.[2]

For smaller, low performance rockets such as attitude control thrusters where high performance is less necessary, a pressurised fluid is used as propellant that simply escapes the spacecraft through a propelling nozzle.[2]

Pendulum rocket fallacy

The first liquid-fuel rocket, constructed by Robert H. Goddard, differed significantly from modern rockets. The rocket engine was at the top and the fuel tank at the bottom of the rocket,[23] based on Goddard's belief that the rocket would achieve stability by "hanging" from the engine like a pendulum in flight.[24] However, the rocket veered off course and crashed 184 feet (56 m) away from the launch site,[25] indicating that the rocket was no more stable than one with the rocket engine at the base.[26]